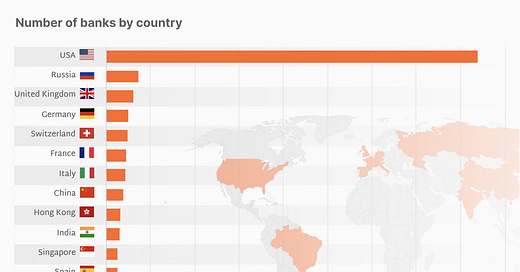

I came across a chart recently which really caught my eye:

The US has a wildly outsized number of banks relative to other countries. This isn’t a complete surprise, I knew the US has always had a lot of banks, but I guess I assumed that with consolidation in recent decades, it was more in line with other modern economies.

Turns out, no! As of writing this, there are around 4,300 FDIC-insured banks in the US. The first reaction to this number might be, like, “the US is massive, and has a ton of people, so it’s maybe not all that surprising”. But even when accounting for population, it still sits far apart from the others.

(Quick note here, all the data we’re looking at is just for banks. The US also has about as many credit unions, and Germany and Switzerland have a lot of them too, but those are worth a separate discussion.)

Looking at the list, another thing stands out: the US has particularly de-centralised political power. That got me wondering, did this more distributed power contribute to America’s outsized number of banks, or did the outsized number of banks help distribute power across the country? Maybe neither? I realised I had some rough ideas, but no single clear answer. I figure we can use the opportunity to dig in together.

So why does America have so many banks? As is weirdly often the case, we have to start with the Founding Fathers.

Two factions

In 1781 the Bank of North America was founded — the first-ever chartered bank in the country. It was first proposed by Alexander Hamilton, primarily as a lever to help finance the ongoing Revolutionary War. Hamilton’s secondary objective was to make the bank the nation’s first national bank, and, by extension, the first central bank. It served its war purpose well, but many pointed to it as proof of congressional overreach, so it re-incorporated under a state charter just 5 years after its founding, preventing it from opening branches in other states.

By the time George Washington was sworn in as President in 1789, two more banks had since been founded in the country, but still operated fully independently of one another, not part of a system as we think of them today. Hamilton was quickly picked to be the first Treasury Secretary of the US, where he laid the groundwork to bring the US in line with other financial systems of the time, implementing the federal revenue system and issuing interest-bearing national debt. To support all this, he created a new national bank, the Bank of the United States, which — crucially — had the power to open bank branches in other states. This allowed the new bank to grow quickly, providing both government funding and commercial banking services.

Meanwhile, looking at the success of the new bank, states began to charter their own banks to help fuel growth. By 1800, there were 30 chartered banks in the country, and more than 100 just a decade later.

Much like its predecessor, from its inception there had been strong dissent among government figures about whether the Bank of the United States should even be allowed to exist. Thomas Jefferson — a strong anti-federalist — was vocal about his concern that a national bank would undermine state banks, creating a financial monopoly, and that the constitution didn’t grant the government the authority to establish such corporations. When the bank’s charter was set to expire, in 1811, there was great debate as to whether to renew it. Many of the of the voices that initially opposed its founding, 20 years earlier, held true to their beliefs. Hamilton was no longer around to defend it, his pro-bank Federalist party was out of power, and the now numerous state banks feared the competition and power wielded by the national bank. By a single tie-breaking vote, Hamilton’s bank was not renewed.

By 1816, Congress realised that a proper national bank was actually quite useful, and created a new national bank, called, reasonably enough, the Second Bank of the United States. After a bit of a rough start (the bank’s workers kept stealing money; and then the bank started a financial panic in 1819), the bank actually came to be a very stable institution. Under Nicholas Biddle, president of the bank, the Second Bank came to take on a new role for the country: it didn’t just help fund the government and open branches, it encouraged the formation of many new state banks, and became a regulator of them and of the broader banking system. This helped buffer the frequent, violent swings in the economy. Biddle was really good at his job. Under him, the American people came to trust banks more than ever, and the period was stable and prosperous. The US was finally on the path to a modern, integrated, financial system.

Which is why, of course, the Second Bank had to be killed as soon as possible. There’s nothing more deeply American than seeing an indisputable success and going “okay, but have you considered this is actually … awful?”.

In 1829, when the bank was at the peak of its success, Andrew Jackson was elected President. Jackson was highly skeptical of anything finance-related. After a bad run-in with a financier, he’d decided that money was silver and gold coins — everything else was a scheme cooked up by bankers to rip people off. So when congress successfully voted to re-charter the bank in 1836, many saw it as a true victory by Biddle, and an affront to the president. Jackson shared that view, declaring to his vice president: “The bank, Mr. Van Buren, is trying to kill me. But I will kill it.” A few days later, Jackson vetoed the re-charter. The bank was dead, and the whole notion of a central bank to stabilise the country died with it.

During this time, state banking had become an increasingly politicised playing field. Banks were chartered by vote in state legislatures, and this opened the door to bribery and corruption. The party in control of the legislature would grant bank charters to its political backers, and block those of opposing parties. By the 1830s, to get away from this corruption, a few states had begun the move to “Free Banking” laws. These laws made the process of granting bank charters an administrative, rather than a legislative one. This opened the door to a new era of banking in the US, where banks cropped up at a faster rate than ever.

The Free Banking era completely changed the landscape of American banking (and is by far the most interesting period of financial history in the US. We’ll be digging into it plenty in coming weeks, so subscribe!). It supplied the country with more cheap credit than ever before as banks competed for customers, but it sent the country into an unstable period — banks frequently ran out of reserves and collapsed overnight. This led to business cycle downturns, and unemployment rose. The key marker of this era was the notion of bank-own currency that each institution created themselves. Rather than the modern system of a single currency shared by all banks, each bank printed its own banknotes, bearing the name of that bank, and would exchange them for silver or gold coins. This, of course, caused plenty of issues for the average citizen, faced with up to 9,000 (!) different forms of banknotes depending on where they did business, and where they banked.

This lasted about 30 years, until 1863. Faced with the instability of the period, and needing a way to finance the civil war, President Lincoln got the federal government into the business of chartering banks once again. Via the newly founded Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the government spurred the creation of new, national banks, who would issue national currency backed by the US government. This cut the legs out from under state banks, now no longer allowed to issue private currency. The new US dollar quickly took over.

Though this initially favoured national banks, state banks were progressively allowed to adhere the dollar model, all while benefiting from low capital requirements to get a charter. And over the next 70 years, the country grew quickly under the government currency model. State and national banks were formed faster than ever. At their peak in the early 1920s, there were about 30,000 banks across the US, holding around 1/3rd of all nominal deposits in the world.

The grand majority of these smaller banks came to be known, over the years, as “Community Banks”. There’s no official definition for these, but it broadly means small banks which serve local populations. In such a vast country, and before instant communication, local banks could better serve their town’s population because they had first-hand knowledge of their clients and their businesses. Local reputations were crucial for deciding who to offer loans to, and who to avoid.

But, you might argue, it seems like this could easily be done by bank branches too, right? Like, the local arm of a big bank can still be run by someone who knows the town well, and can make the same informed decisions — just, now they’d be backed by the safety of a major institution. Anyway, this is how most of the world operates — a few big banks, and a load of branches. What makes the US different?

Banks and branches

Mostly, it’s because creating bank branches was just really hard throughout most of US history. Much of the US government’s thinking around banks has historically gone something like this:

The country is huge, and the population is very spread out…

That population needs easy access to banks to grow local economies…

We should encourage those banks to be unit banks, rather than branches…

Why? Because more unit banks is better for competition, and aligns the incentives of the local banks with the local populations.

From the days of Hamilton’s banks, both state and federal laws set heavy restrictions on how many branches banks could operate. Particularly, state banks were almost always limited to creating branches within their own state, which hampered the drive to create a strong branch network. Even national banks were, frequently, quite restricted in their ability to branch out-of-state, largely due to what’s now considered a misinterpretation of Lincoln’s National Banking Act.

The theory goes that individual, smaller, unit banks better serve rural communities than branches can, because of their aligned incentives. What’s good for the bank is good for the town, and vice versa. A major concern of lawmakers was that big banks would take deposits in their new rural branches, and immediately send off those deposits to a faraway city where the bank was headquartered. It would draw capital away from rural areas in favour of urban centers.

And mostly, rural clients agreed. Through most of the country’s history, farming was a leading profession; rural landowners had a strong incentive to favour unit banks to have a better chance at getting loans. The fear was that a large bank could open a branch in a farming community, draw away clients from local banks because of the stability the big name represented, happily take deposits, but issue fewer loans than a local bank. If you’re a large national institution with branches all over the country, why would you lend money to the farmers of Greenfield, Missouri — who might lose all their crops to a bad season — when you could lend to middle class New Yorkers? The risk/reward is just not worth it.

Favouring unit banks made sense for local governments, too. By making their area attractive to new banks, towns invest in themselves: any subsidies, in theory, pay for themselves as the new bank helps finance more local businesses, making the region more attractive, and the tax revenue from those businesses helps to grow the town. That same government can be reassured that, unlike a branch which could be killed overnight by a cost-cutting exercise in the parent bank, a local institution has a vested interest in the area, and is more likely to help the community weather economic downturns.

This vision of small-town banking in the US persists in the modern day. In 2007, Fed Governor Randall Kroszner shared in his own words:

“Community banks continue to thrive by providing traditional relationship banking services to members of their communities. Their local presence and personal interactions give community bankers an advantage in providing financial services to those customers for whom, despite technological advances, information remains difficult and costly to obtain…”

Community banks are a staple of the American banking system, and multiplied fast. Things are changing, though.

The downtrend

By the 1980s, banking, like many sectors, reached a turning point. Money market funds — offering higher returns than deposit or saving accounts — were attracting more investment than ever, at the expense of tightly-regulated bank accounts. The banking system’s share of the US financial system was shrinking quickly.

Banks and their political supporters responded by calling for deregulation. Bank mergers, which had long been viewed as anti-competitive, were increasingly allowed. Large banks could now much more easily acquire smaller banks across state lines, driving rapid consolidation.

The following decade, the Riegle-Neal act was passed, removing many of the restrictions on opening out-of-state branches, fuelling consolidation and marking the rise of regional banks. Unit banks were increasingly brought into larger financial holding groups, operated more in line with the branch model from earlier — the individual banks can be spun off or restructured to support the larger company.

In parallel, capital requirements have grown over the years, making the barrier to entry for new unit banks higher than ever. Tighter regulation places a higher cost on all participants — prohibitively high for new entrants and smaller incumbents, while larger, entrenched players can more easily stomach the cost.

Locality is also much less important than it was in past decades. Online banking removes much of the need for regular visits to a physical location, favouring larger banks which can minimise investment in physical branches. Economies of scale work out in favour of the larger banks here, too, as the fixed costs of their online banking infrastructure are spread out over a larger client base, where a small unit bank will struggle to keep up.

And the numbers confirm that trend toward consolidation in the last decades.

The 5 largest banks in the US now hold around half of all commercial bank assets in the country. In contrast, banks with less than $1 billion in assets controlled around 6% of deposits in 2022, a steep drop from their near 10% in 2016.

What does this mean for depositors?

Even if things are trending toward concentration in recent decades, the US still has more banks than elsewhere, at over 1.2 per 100,000 people compared to the sub-0.4 EU average.

This, in theory, should mean increased competition, suppressed profitability, and lower end-customer fees in US banks versus comparable Canadian and European players, right?1

Well, mostly, no. US banks are on average still significantly more profitable than in other regions. There are two key ratios to look at here.

First, Return on Assets (basically, how much profit does the bank generate for every dollar of assets they hold?). By return on assets, US banks have outperformed Canadian and EU banks almost constantly in the last two decades.

And secondly, Net Interest Margin (how profitable is the difference between the rate at which the bank lends money and borrows money?).

Here, too, the US outperforms, though this is more attributable to higher average lending rates in the US than in the EU and Canada — particularly in credit card lending and mortgage lending. Competition aside, US banks benefit from macro factors that make them more competitive than in other regions — a confluence of higher lending rates, and much more relaxed regulation, allowing for a higher return on assets.

That lax regulation highlights another, crucial aspect of consumer banking services where US banks lag behind despite heightened competition: interchange fees. This is a fee charged by your bank to a merchant each time you pay by card (and so is factored into the end prices paid by consumers). It’s the largest fee — though indirect — most consumers pay for their bank services.

The EU has set tight caps on the legal maximum interchange fee issuer banks can charge, while American regulation has been relatively toothless, leaving it among nations with the highest card processing fees. US banks have opted to just not compete on this front.

Competition among so many banks is only as beneficial for consumers as the regulation which supports it.

So, returning to our original question: the main reason the US has so many banks really is because it’s so huge and its power so distributed.

Branch banking, at a glance, looks to be the ideal model, given such a spread out population, but it’s the combination of political choice, American skepticism of central power, and the country’s wildly diverse regional economics which fuelled the rise of the thousands of individual banks around today.

In a country whose landmass has, historically, primarily served small farming communities, this model has had its upsides. But this weak (though growing) concentration poses issues today. Smaller, local banks are — by definition — less diversified in their risk base. They face many (though not all) of the same fixed costs as the major institutions, but don’t enjoy the economies-of-scale upsides. This passes on the costs in the form of higher loan premiums and lower savings account rates. Banks are acutely aware of the stickiness of their service for the average depositor, and so are little pressured to compete on price. The increased competition of the US’ many banks is not only not lowering prices for end customers, the instability it causes threatens to actively increase them.

The US has always had a penchant for doing things differently. But in this case, nothing points to it doing things better.

Obviously Canadian and European banks aren’t the only other systems in the world, but they’re the only directly-comparable regions in terms of broad regulation initiatives. Comparing with Asian or African banks makes an apples-to-apples comparison more blurry.