There’s a lot we take for granted about the way our money works. It seems obvious that a $10 bill should work the same way whether you’re in Los Angeles or New York. It might not buy you the same amount of stuff everywhere, but everyone probably agrees that your $10 bill is, like, worth $10.

And for the most part, the same thing applies to how that bill looks. Even if it’s a bit scuffed, maybe got a slight tear on a corner, as long as it’s in reasonable state, only the number on the front really matters.

But there’s no rule that says that currency should naturally be interchangeable — or, fungible — by default. Consider Madagascar in the early 2000s:

Although it has its own currency, the Malagasy Ariary, many workers in Madagascar prefer to be paid in stronger foreign currencies like the Euro or the US dollar. This means other currencies — namely the dollar — circulate fairly widely on the island, as businesses are happy to take foreign currency versus the local, weaker, cash.

But around 2006, when those workers would go to spend their dollars, many began to sense that local businesses were less eager than before to take their banknotes. Shopkeepers would take a closer look, inspecting the bills before accepting them. Were they checking for counterfeits? Not exactly. They were looking for something more specific: a small signature.

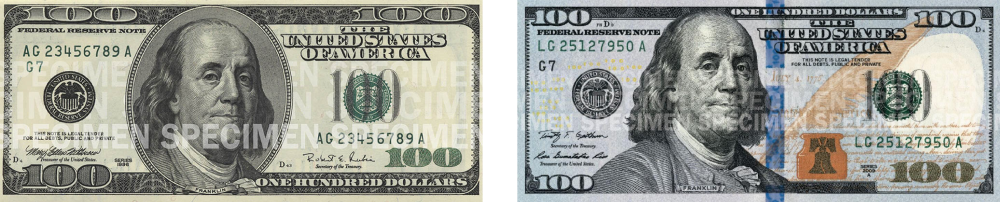

On all modern banknotes, there’s a bunch of different details, security features, serial numbers, and plenty else that help keep track of which bills are in circulation, and to minimise fraud. One of those details, on every dollar banknote, is the signature of the sitting U.S. Treasury Secretary at the time that note was printed. This is mostly a formality from the early days of note printing in the US: at least one signature has appeared on all paper money since the mid 1800s.

And when shopkeepers took a closer look at the notes, it’s this signature they were looking out for. They weren’t checking whether or not it was there, but whose signature it was.

Their check could go one of two ways. If the signature looked like this:

then they’d happily cash the note. But if the signature looked like this:

then they had a problem.

On that first note is the signature of John. W. Snow, Secretary of the US Treasury from 2003 to 2006. The second belongs to Robert Rubin, also Treasury Secretary, but from 1995 to 1999.

What those workers quickly understood was that shopkeepers and traders in Madagascar were using these signatures to directly determine how much that note was actually worth. A modern, Snow, bill was worth face value — the amount printed on the front. But a Rubin, barely 10 years older, was worth a more arbitrary amount — not nothing, but certainly less than a Snow. Some merchants discounted the bills by as much as 15%, if they accepted them at all.

If you’re a Madagascan worker, and you’re paid your salary in US dollars, this is obviously not a great situation. Depending on your luck on payday, your $500 salary might turn out to be more like $425 by no fault of your own.

And it’s not even like you can really make a fuss to your boss either: they promised you $500 in cash and that’s what you got. Nobody’s really in the wrong, but it still feels like you’re not getting what you were promised.

Which brings us to the obvious question: in the US, a dollar is a dollar, regardless of what it looks like; why wouldn’t it be the same everywhere?

To answer this, we need to briefly zoom out and remind ourselves of a core principle about money in any form: it’s only as valuable as people’s willingness to accept it. In other words, it’s only as valuable as its ability to acquire goods and services.

This seems obvious on its face. Basically everything we can acquire or get rid of, we implicitly think about in equivalents of money. In the West, we rarely have to pay much thought to the medium of exchange itself — the actual money we use to transact. The value of my cash is evident, I don’t have to convince anyone of it. I know this shopkeeper will treat my $10 bill as being worth $10, because they know that when they go to spend it, their supplier will also value that bill at $10, and so on.

Continue that line of thinking long enough and you’ll quickly arrive at the very tricky question of why we should believe those $10 are ultimately worth anything at all. There’s no one simple answer here, and we’ll dig into all the different theories about that in a different post.

The key point is that, in a country where only one currency is widely used, all parties take the face value of the bill as the key input to determine its market value. There’s no real alternative means to acquire goods and services, so I know (mostly) everyone else around me will accept my cash, and will all agree with me on its value. In other words, my banknotes are perfectly liquid: they’re abundant, and I can easily “convert” them into goods and services.

But anywhere my dollars aren’t the exclusive currency, or even just not the most widespread, I might quickly find it harder to convert my notes into the things I want. Suddenly, I can’t be so sure that my trading partner will want my dollars. Assuming all I have are US dollar banknotes, and we both want to settle the trade immediately, there are 3 possible outcomes to a transaction we want to carry out:

I want to pay in USD, and my partner wants to be paid in USD: great, we can do business!

I want to pay in USD, but my partner will only take a different currency

I want to pay in USD, and partner wants to be paid in different currency, but they’re flexible, they’ll accept USD for the right deal

If my trading partner, for whatever reason, thinks they’ll have trouble spending the dollars I give them, those dollars are worth less to them than a currency they know they’ll be able to spend easily.

In the Madagascar story, it’s not even two different currencies that are at odds; it’s two editions of the same currency. But the logic is the same: if my partner thinks they’ll have a harder time spending Rubin dollars than they would Snow dollars, they’ll do all they can to be paid in Snow dollars. And if they do accept Rubin dollars, they’ll try to get them at a lower price than the more liquid Snows.

This is a prime illustration of a liquidity discount. If two identical assets trade on a market, but one of them is harder to convert to cash (or goods and services directly), then this less liquid asset will trade at a discount. So when a $10 dollar Rubin bill trades at a 15% discount to a $10 Snow bill, it essentially means that the market has decided that the relative ease of trading a dollar note is worth $1,50. Any bills that that aren’t as easy to trade are, by definition, worth less.

And as Madagascar illustrates, the reasons to believe people won’t want to take your dollar note can be basically … anything.

If the bill is a little ripped, you might assume the next person will be more hesitant to take it. Maybe it doesn’t have the same security features as the newer notes? You might worry that banks won’t accept it. Or what if my note is getting old and has a different visual design to the newer, more common ones: what if traders decide to stop taking it?

These aren’t made up examples. Lebanon faced a problem just like this in 2021, when a handful of money exchangers decided to stop accepting $100 bills issued before 2013, when a new design — the Blue dollar — was introduced. Quickly, not wanting to be left holding worthless notes, other money changers followed suit, either discounting or outright refusing the pre-2013 notes, on the grounds that there was less customer demand for them.

If you have no good way of using those dollars in trade with someone who will value them at par (either a US entity, or someone who does business with the US, etc.), then you’re left hoping that the next local will value the bills as much as you do. And for island nations like Madagascar, fairly isolated from the US, you’re mostly left relying on the the local crowd or money changers.

It doesn’t matter whether the reasons for arbitrarily discounting your cash are self-imposed. It doesn’t even matter if your American embassy publicly tries to assure you that all designs of a given note are worth the same. If you think others won’t treat them equally, you won’t either.

How do other countries do it?

It’s worth noting that old and new dollars being completely interchangeable is more the exception than the rule, on the global scale. Most countries are far less generous when it comes to being able to exchange all types of old notes.

In fact, as far as I can tell, the US is the only country which has never deprecated its older-style currency. It’s withdrawn plenty of older designs and denominations from circulation, but it’s policy that all currency remain legal tender regardless of when it was issued. Currency in the US has a fascinating and complicated history, which makes this makes this flexibility extra impressive. (We’ll be exploring lots of these stories in future newsletters, so subscribe!)

Similarly, the EU has sunset and withdrawn older-style notes, and has stopped making the 500€ note entirely. In fairness, no Euros have ever been fully deprecated either — you can still trade all old Euros for new. But the EU isn’t a country, and member countries all deprecated their original currencies, so they don’t count. In any case, the Euro’s much younger than other leading currencies, so looser rules around convertibility are perhaps to be expected.

Credit where credit is due, Japan explains that all old banknotes never stop being legal tender. But they then immediately follow up with a list of all the times old banknotes stopped being legal tender.

The more you dig, the more the US looks like an outlier in its flexibility around what counts as valid cash.

The UK has withdrawn plenty of notes and coins. Many are no longer legal tender, and won’t be accepted by businesses or banks, but lots of old notes can still be traded in directly to the Bank of England. Coins are harder to get rid of though, and the Royal Mint offers comically little advice about what to do with them.

China accepts some old Renminbi, but only back to the 4th series, from 1987. Elsewhere, countries with a history of volatile currency are usually quick to orphan old notes and coins, and countries who’ve faced widespread counterfeiting have good reason to cut off old bills.

Most countries aren’t as generous as the US in their support for old notes, and even then, Madagascar shows us that problems can still crop up. Which leads us to our main question:

What can you do to fix the split?

Let’s go back to our story from before. One day, you wake up to find that half of your cash is worth a fair bit less than yesterday. Where does that leave you?

Well firstly, it’s confusing. In highly-banked countries, knowing how much money you have ready to spend now is pretty straightforward — you can look at your bank accounts to get a solid overview. But in Madagascar, access to financial services is extremely limited.

Less than 10% of adults held a deposit account in 2017. This figure was more like 5% in 2011. If you don’t have a bank account, then the majority of your (liquid) wealth is likely made up of just cash. If half this cash is arbitrarily worth less than you expected, you’ll have to spend time and effort to figure out the total value of your banknotes in terms of new money. This makes spending decisions harder, as how much money you “have” depends on who you’re buying from. It makes saving money a challenge too, as you have no guarantee that the cash you stow away will still be accepted even in even a few months, let alone a few years.

Secondly, and directly related to the last point: it further hampers financial inclusion. In a country already struggling to access banking services, a bank arbitrarily deciding they won’t accept your cash as a deposit raises this barrier to entry even higher.

Banks aside, it’s bad for business too! What would normally be a straightforward transaction — i.e. I pay a dollar bill for a dollar’s worth of goods— now becomes slower and more complicated. Just having a dollar bill isn’t enough, it needs to be the right dollar bill. Suddenly my regular purchases have just gotten 10-20% more expensive without the price ever changing. Shopkeepers have to spend time evaluating each bill they’re handed, checking it for age, quality, and weighing up the odds that they’ll have trouble spending it. This means extra fees to offset risk, growing lines at checkouts, and more time required to manage the books under a split currency.

So how do you fix the problem?

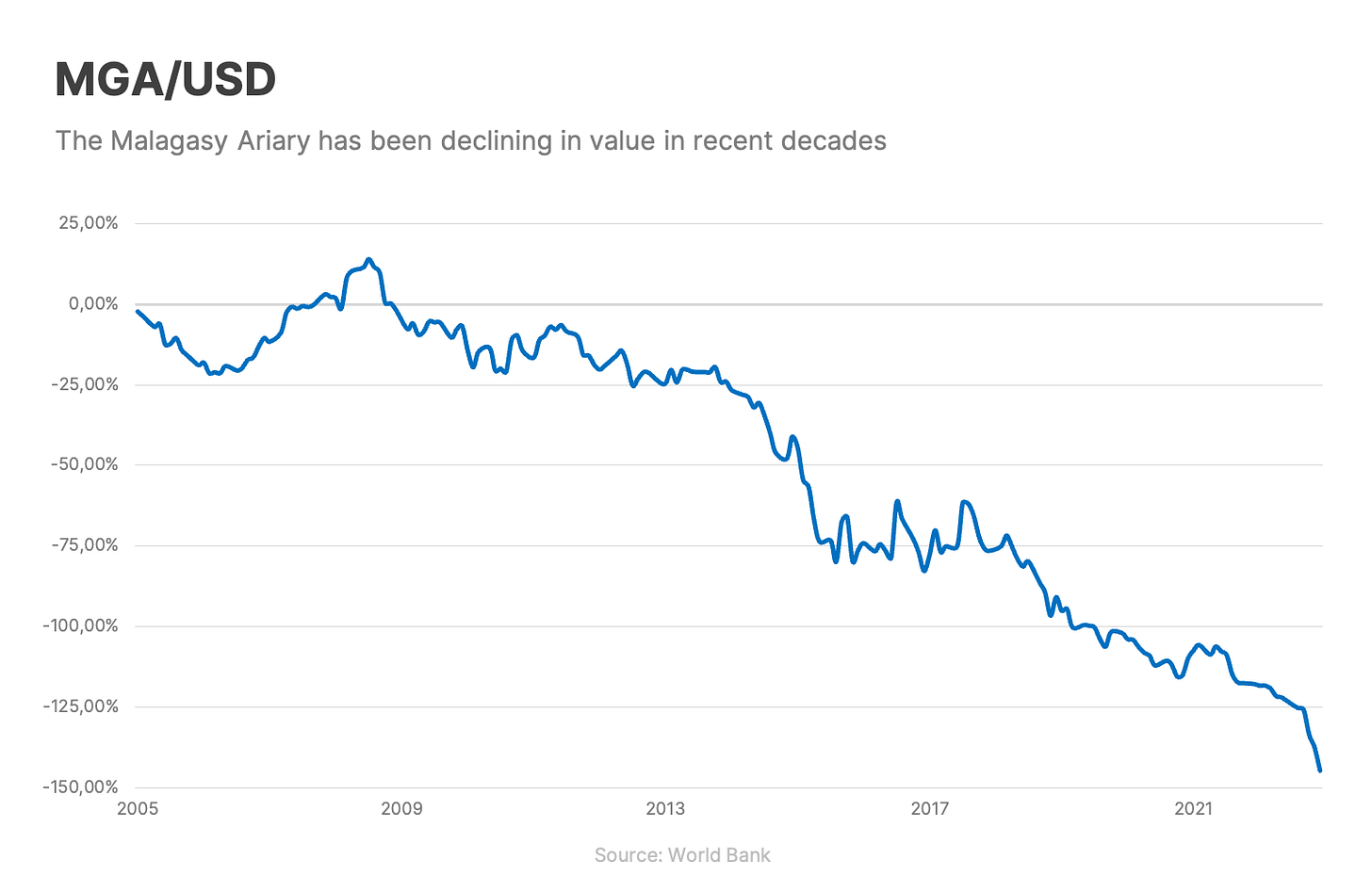

If this is only a problem with foreign currencies, because you can’t trade them in to your government directly, the obvious answer would be: stop using the foreign currency! If I just start using the local Malagasy Ariary instead of these foreign dollars, then I avoid the problem entirely. And that’s sort of true, but it’s easier said than done. The average worker in Madagascar rarely has much leverage to dictate how they’re paid. And anyway, workers paid in dollars are — in normal times — usually pretty happy with that arrangement. The alternative is to be paid in Ariary like most people, which has more than its fair share of problems:

The local currency has cratered in value over the last couple of decades, meanwhile consumer prices have consistently grown over the same period.

Split value cash, or high inflation. Pick your poison.

If dollars are going to continue circulating in some form or another, you could argue that the country’s central bank could step in. One scenario you could imagine is that the bank could announce that they’ll use their currency reserves to support the full convertibility of old dollars for new dollars — either directly, or indirectly via retail banks. In theory, this mark of faith by the government would reassure individuals and businesses that they can safely value both types of notes at face value again. Gresham’s law wouldn’t kick in, as the government doesn’t control that currency’s monetary policy, they’d only be reiterating the policy of the issuing government.

But could that work? Let’s assume the central bank has a good way of converting their foreign reserves to physical cash, and the right type of it, and that people believe that the central bank can get their hands on enough new-style notes. Even then, this approach still isn’t bulletproof. In perfect theory, nobody would have reason to go to the central bank to convert their notes, because just the knowledge that they’re fully convertible should be enough to cement their value. But in practice, a population that already struggles to access retail banking will have a very hard time reaching a bank to make the conversion. Transaction costs are real, and have a distorting effect on policy. Unless you’re 100% sure that you and everyone else can convert your old bills to new ones for free and at a moment’s notice, you’ll continue placing a premium on the bills you know everyone prefers.

To at least try to smooth over the problem a little, the government could push merchants to actively display multi-tiered pricing based on the types of bills used. This idea would be far from new, and would at least help avoid confusion and extra waits when going to pay. But honestly this isn’t much more convenient than before. Sure, it’s less confusing for individual dollar holders, and saves a bit of time for merchants (once they’ve found the time to make all the signs they need), but it could also have an adverse effect.

On one hand, prices in old Rubin dollars might stabilise, as their value is now more transparent, and merchants will more easily align on each other’s prices. On the other hand, proactively showing tiered pricing risks further legitimising the idea that the Rubins are inherently worth less, and could further drive down their value. Money changers would be even less inclined to accept old bills if they don’t expect to trade them overseas. And what does this mean for outstanding debt? If your debt to a local supplier is just to be paid in “dollars”, you and your creditor will quickly disagree on what type of dollars that contract implied, the first time you try to hand them Rubins.

Any direct intervention into the market risks creating as many problems as it solves. Once this type of split sets in, there’s really only one way it can be solved: let the problem fix itself. On a long enough timeline, market participants will take care of the issue on their own. Businesses able to trade with foreign markets will happily accept the old dollars, as they know they can turn around and offload them at face value.

In Madagascar, it was off-license money changers who took up the arbitrage opportunity. Registered changers could refuse old notes, but they weren’t allowed to discount them. Unlicensed traders faced no such issues, and happily took the notes at a price somewhere between local market value and par, then traded them abroad at their ‘real’ value. On a long enough timeline, these businesses and changers will take in all the excess old notes from circulation, ship them where they’ll be more favourably valued, eventually leaving only “good” notes in the system.

An arbitrage opportunity, however obvious, is only as valuable as your ability to execute it. If you’re a Madagascan worker paid in Rubins, far removed from the world’s financial system, it’s not enough to spot the opportunity if you can’t do anything about it.

Anyway, money’s complex. We usually do a pretty good job of coordinating the balancing act of policy, financial infrastructure, technology and all the rest such that it mostly just works in the background. It’s only when one of those parts breaks down that we realise how much of the complexity of money we usually get to ignore. Maybe a dollar being a dollar, in Los Angeles or New York, is a feat worth celebrating.

If you’ve made it this far, I hope you enjoyed this first edition of Blind Trust! My goal with this newsletter is to explore interesting stories about money, and (hopefully!) spark in others a similar curiosity for the puzzling ways it works.

If that sounds interesting to you, I’d love to have you along for the journey!

(Next post, we’ll be looking at a strange recent announcement by Brazil and Argentina, and trying to answer the question of what makes two countries want to share a currency. I hope to see you there!)