First off, welcome to all the new subscribers since launching Blind Trust, I’m very grateful to have you on board! This week, we go a little bit more economics-y, and take a look at currency unions.

A few weeks ago in Buenos Aires, Latin American countries held the yearly CELAC summit. The summit is an opportunity for neighbouring countries to come together to publicly discuss policy plans, strengthen ties in the region, and push new integration initiatives.

Ahead of the event, countries usually announce what they’ll be discussing and what their main priorities look like for that year. And this year, two neighbours certainly didn’t disappoint: a few days before the meeting, the heads of state of Brazil and Argentina issued a joint announcement — they would use the summit as an opportunity to find ways of strengthening ties between their two “sister nations”. Routine so far, but in the list of various policy points they’d discuss, one item stood out in particular:

[…] We also decided to advance discussions on a common South American currency that can be used for both financial and commercial flows.

This caught a lot of attention in the media and on Econ-Twitter, with most reactions looking something like this:

And it wasn’t only pundits and policy wonks that found it surprising. Brazil’s central bank seemed to be taken by surprise on this one, too. Executive Secretary of the Economy Ministry, Gabriel Galipolo, was quick to downplay the announcement, adding that the proposal “has nothing to do with replacing national currencies”. Finance Minister, Fernando Haddad, said much the same, that it would serve only as a “common payment tool for trade”.

But by the sound of the initial announcement, it’s clear that the two countries have a larger ambition for a shared commercial currency at some point. Haddad himself co-authored a paper in 2022 which called for a “process of monetary union in the region”, where members could adopt the new currency, named the “Sur”, for domestic use too. It wouldn’t be the first time the two countries have explored developing a common currency, either. More on that in a bit.

Whether or not the two countries actually go ahead with their currency plan is up for debate, but not the main focus for today. I think the more interesting question is “why does everyone seem to think a full-blown common currency is a crazy idea?”. To answer that, it’s worth first having a clear understanding of why countries would even want to have a common currency.

What’s the point of a currency union?

Adopting a shared currency means, by definition, giving up some amount of control over your country’s monetary policy. Either you adopt a foreign currency, and are subject to the issuer country’s domestic monetary policy, or you establish a new central bank of your own, which will govern policy for the union. Either way, policy for your own currency is no longer set by your country alone.

But obviously there are upsides to this tradeoff, which we can broadly categorise into two buckets: global advantages, and local advantages.

On the global side: shared currency helps attract foreign direct investment. The Eurozone serves as a good base of comparison here. Baldwin et al. (2008) found that even when controlling for non-currency-related, pro-integration policies, the adoption of the Euro appears to have had a tangible effect on growing FDI from outside nations to EU member countries. This supported previous research like Petroulas (2006), which estimates that FDI from non-member countries grew around 8% due to Euro adoption in the immediate years following EMU integration.

A shared currency means a larger potential market for foreign investment which translates, in theory, to heavier sway in foreign trade relations.

And there are lots more internal benefits. Just as a currency union attracts outside investment, it fosters trade within the union, too. It’s hard to put an exact number on this, but building on Eurozone research from HM Treasury, and Barr et al. (2003), a paper by De Sousa and Lochard (2006) found a lift in bilateral trade as high as 30% in their study of 1992 to 2005. The logic is basically: foreign trade incurs currency risk and transaction costs; removing this uncertainty helps promote investment and trade between member states. Prices are made more transparent, too. This particularly benefits smaller firms and individuals, who can shop around more easily, no longer bound to their domestic market. This then encourages competition between member states, promoting efficiency on the producer side, and lower prices for the end-customer.

It’s important to note here that in their international trade, most countries already use a shared currency — the US dollar. This adds an extra reason countries can be eager to form a new shared currency alliances. Using the dollar in trade, regardless of where you are, places you under the jurisdiction of the US Treasury. In recent years, the US has increasingly used this privilege to ‘weaponise’ the dollar as a political lever. Even if neither you nor your trading partners are at risk of US sanctions right now (and this can change very quickly), the extra control offered by your own monetary union somewhat helps de-risk that position.

So there are real, measurable benefits to a currency union done right. With that in mind, we can start to look at the previous question of why everyone thinks the Sur would be a certain failure. Theory can guide us here.

What makes a good currency union?

The tricky part of evaluating whether a given currency union will work or not is that we really don’t have many successful ones to use as blueprints.

Basically the only major union we can use as a point of comparison is the Eurozone. And even then, there’s only so much we can learn from it — every region is different, with its own economy and business cycles. What worked for the Euro won’t necessarily work for the Sur, the West African Eco, nor any other planned union.

But the absence of data instead gives us an opportunity to explore some interesting theory in the space. Most of today’s thinking around currency unions is largely based on Canadian economist Robert Mundell’s work on “Optimal Currency Areas”, published in 1961.

In the paper, Mundell concludes that currency unions can help maximise economic efficiency, but only if its participants meet 4 key criteria:

A large, available, and integrated labor market

Workers must be able to move freely throughout the area, so as to balance out unemployment in any single region. This means removing administrative barriers like visas to travel between countries, and allowing workers to contribute toward retirement funds even while working abroad in other member countries.Flexible prices and wages, with no capital controls

Prices and wages must be set by the market to avoid trade imbalances between regions. And within the union, money needs to be able to flow freely across borders to maintain a single value for the currency.Currency risk-sharing mechanisms

Some form of central authority (e.g. a central bank) is needed to be able to redistribute wealth around the union, balancing out the economic difficulties of one region with the the surplus of another. This one’s pretty unpopular among nations. Actually, many argue that the European debt crisis of the early 2010s was largely due to the Eurozone not following this requirement. Original EMU policy included a no-bailout clause, which initially prevented the EU from redistributing revenue from stronger regions to support weaker ones.Similar business cycles

The union’s central bank, by definition, will be setting monetary policy uniformly for the entire area. Members need to have at least reasonably-correlated business cycles to avoid one region being harmed by the same policy which benefits another.

These principles were proven quite prescient, given that the research was published in the Bretton Woods, fixed exchange rates era, where the subject was more a theoretical experiment than an applicable strategy.

Of course, these requirements aren’t necessarily the only factors that ensure a successful currency zone, and anyway, this is all still theory. Over the years there have been various proposals to add extra criteria to this list, based on newer — sometimes conflicting — research. Some of these suggestions include things like the need for a high volume of trade between countries to make the new currency worthwhile; or that member countries should each avoid heavy specialisation in any one sector, so as to better absorb shocks.

In any case, the 4 main requirements have so far held up pretty well. The EMU has cited Mundell’s work as having served as a blueprint for the union, and later research has supported much of his original theory, ultimately earning Mundell the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1999.

So let’s now turn back to the Brazil-Argentina thing. We can use OCA theory as the lens through which to look at the announcement, and begin to weigh up what a potential union might look like.

Could the Sur work?

This isn’t the first time that Brazil and Argentina have been vocal about pushing for a common currency.

In the late 1980s, the leaders of Brazil and Argentina signed a joint proposal initiating the creation of the Gaucho, a common currency to be first used for regional payments, and to be the basis of an “entire and durable monetary integration”. The two countries’ central banks were to create a jointly-administered “Reserve Fund” and quickly set up agreements for implementing the new currency.

The plans quickly came to a standstill, as inflation in both countries took off again after a brief period of relative stability, and focus turned to each first solving their domestic problems rather than exploring cooperation ideas. A few years later, the Mercosur trading bloc was created, including both countries; Brazil instituted the Brazilian Real, and plans for further monetary integration fell by the wayside.

So it didn’t work out then, but how are things looking today? Let’s start by looking at the four main OCA factors.

First up, a large and integrated labour market. Brazil and Argentina, and much of South America more broadly, are pretty solid here. Immigration statistics for Brazil have Argentina in the top 3 countries of origin.

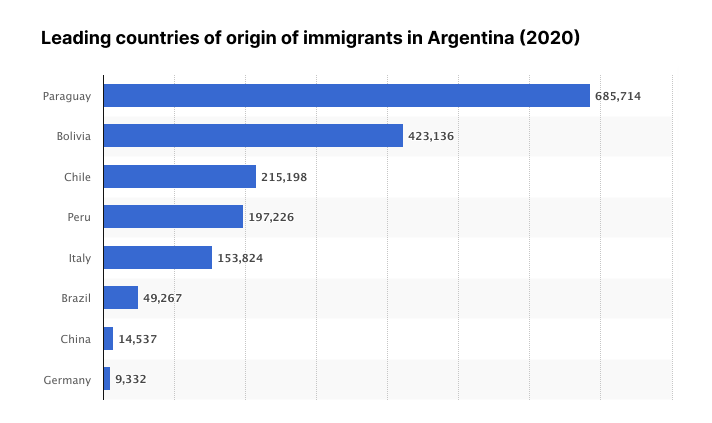

Conversely, approximately just as many Brazilians migrated to Argentina in 2020; Argentina just takes in a lot more migrants from other neighbouring countries, pushing Brazil out of the top 3.

This is largely due to the Mercosur Residence Agreement, which allows citizens of Mercosur states to live and work in other member states with very few requirements. Workers can usually be employed in other countries without even sponsorship from an employer.

Brazil and Argentina aren’t each other’s largest destination for emigrants, but they have very accommodating policies in place for neighbour-state migration. They both broadly tick the first box of OCA theory.

Next up — flexible prices and wages, with no capital controls. This one would depend on specific policies defined for the union, but we can look at how both countries operate today to get an idea of what a union would entail. Both countries are strong market economies and would continue to operate as such. Actually, Brazil and Argentina are similar countries in a lot of ways.

Their GDP per capita (constant $) are broadly similar, and relatively correlated.

Course GDP per capita alone doesn’t tell the whole story. But in inflation-adjusted PPP prices, both countries have a relatively similar median incomes. Argentina’s data is for urban populations only, but both Brazil and Argentina have fairly similar urban population rates (92% and 87% respectively).

But real prices in both countries are facing very different outlooks.

Roaring inflation and ever-strong strong capital controls make Argentina a difficult partner for a strong union — at very least a heavily unbalanced one, which brings us to the next point: currency-risk sharing mechanisms.

This one’s a real hypothetical in the case of Argentina. The Argentine government has fuelled its spending by aggressive money printing for decades — largely in order to roll on its debt, while Brazil runs an independent central bank targeting monetary stability.

Unless both countries can agree to, and actively enforce common fiscal prudence, the currency-risk sharing will lean heavily in Argentina’s favour, given a government long accustomed to aggressive spending. Brazil is a net creditor globally, with deep currency reserves, while Argentina’s still facing a balance of payments crisis, running on growing loans from the IMF. This would immediately put pressure on Brazil, who — same as in the Eurozone example — would find itself bailing out its neighbour to sustain the union.

Right now, Brazil enjoys the benefits of having its own monetary authority, and would be the stronger of the two partners. If the monetary union went ahead, Argentinian debt would presumably see its risk premium soften, as investors would see Brazil as a backstop. But realistically, would Brazil play that role, given the imbalance right from the start? There’s no economic argument for it.

So what about business cycles? Export markets for both countries are pretty uncorrelated, mostly due to the countries’ vastly different export markets. Though both are large agricultural exporters, Brazil’s largest share of exports are focused on petroleum and mineral products,

while agriculture represents almost half of Argentina’s exports.

And how about trade with each other? Things continue to skew heavily against Brazil. Argentina is much more reliant on Brazil for both imports and exports than Brazil is on Argentina.

Looking at the European Union again, the major countries of the union already had strong trade relations long before the move to a shared currency, owing to postwar economic and industrial policies aimed at building regional interconnections. In the case of Brazil and Argentina, things are different: trade between the two countries is reasonably strong — accounting for around 6% of their combined GDP — but the heavy imbalance, again, sets relations on shaky footing.

With regard again for OCA theory, at least both countries’ overall GDP trends are broadly correlated, with Brazil slightly leading the cycle.

So definitely not a perfect match, but not worlds apart. The larger challenge in the short-run for both countries would be managing the transition to a joint monetary policy. Because of the vastly different inflation situations in both countries, key rates have responded in turn, driving the two countries’ rates further apart than almost any time in the last 2 decades.

Committing to a joint rate target would be a painful transition for Argentina. Again, we can look at this situation through the lens of the Euro. The Maastricht treaty outlined a number of “convergence criteria” for any country aspiring to join the union, one of which set the following requirement:

[…] a Member State has had an average nominal long-term interest rate that does not exceed by more than two percentage points that of […] the three best performing Member States in terms of price stability

In our case, there’s no existing bucket of countries against which to compare rates, but similar rates appear critical for countries aiming for a union. The theory, at least, is that if countries can converge their monetary policy, they’ll be able to converge their domestic market behaviours, which will smoothen the transition to a joint model. It’s worth noting that there’s a large school of thought which argues that convergence isn’t really required ahead of a union, and that countries are likely to basically force nominal figures to meet the requirements anyway, regardless of real impact. But we have no good examples of if this would work in practice — Europe’s still our best point of comparison so far. In any case, what the current divergence in rates mainly illustrates is one country’s significant instability compared to its neighbour. Not an obvious contender for a union.

So things aren’t looking likely anytime soon for Brazil and Argentina, and that’s probably for the best. Having a forever-unstable neighbour is problem enough, let alone being handcuffed to them. Reviving this common currency project is based more in political signalling than economic reason, as Brazil’s recently re-elected President pushes ahead with his ambitions of increasing Latin America’s geopolitical weight via stronger integration throughout the continent. And if you’re Argentina, any lifeline looks good in a dire situation.

Anyway, this specific case is just an opportunity to look at the larger picture of currency unions. It’s worth keeping in mind that OCA theory, as useful as it proves, is still just a tool — a framework for thinking about these major decisions. It’s frustrating that we have so few examples of major unions to compare against, but at least it leaves us room to think about what could be.

The implicit conclusion of Mundell’s theory is that it’s almost always best for countries to maintain independent fiat currencies with flexible rates, and that’s what most of the world looks like today. But that “almost” leaves room for potential union success stories. The Eurozone has had its fair share of struggles, but by many accounts has been a net-positive for member economies. Sure, Brazil and Argentina are an extreme example, but the upshot is that the whole idea of large-scale currency unions is still very much in its infancy.

Sure, most proposals are set to fail — these things are hard — but that just means there’s still lots to learn!